Eating for Mental Fitness

How to Improve Well-Being with Proper Mental Nutrition

We all know that low-quality foods lead to bad health. What few of us stop to consider is that low-quality mental foods lead to bad mental health, too.

Food serves as an input to our body’s physical processes. Likewise, information serves as the input to our brain’s mental processes. And if the inputs are bad, no amount of brain-power can turn them into good outputs.

Unhealthy Trends

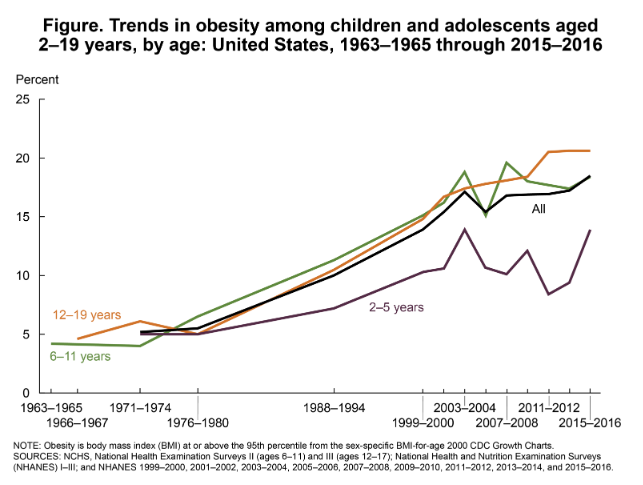

The obesity epidemic is a constant reminder that our diets leave much to be desired. A quick glance at this chart illustrates the point:

We know there’s a cause-and-effect relationship between consumption of junk foods (i.e. sodas, candy or other highly-processed snacks) and obesity. We know that children and young adults are especially vulnerable, because they don’t have pre-existing habits to fall back on.

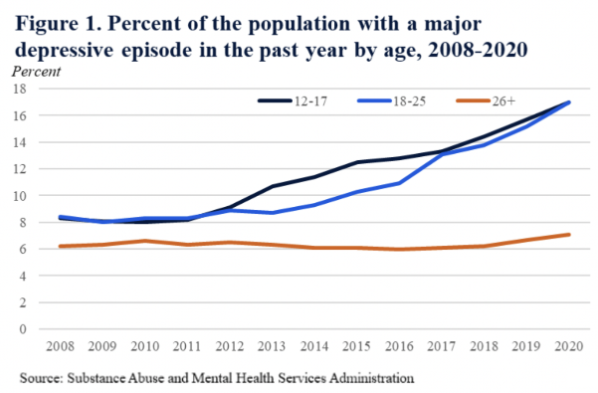

Likewise, it should be obvious to us that when we see this chart:

The likelihood is quite high that there’s a similar cause-and-effect relationship in place. People, and especially young people, consume junk information. Junk information is addictive. And it is wreaking havoc on young people’s mental health.

Unhealthy Mechanisms

Besides the obvious similarity in trendlines, these processes have another trait in common. Junk information – whether it comes in the form of clickbait, partisan invective or dancing cat videos – triggers the same dopamine spike in our brain that sugar does. And just as with sugar, the vicious cycle of craving->action->reward->craving tends to accelerate over time until it becomes a full-fledged addiction.

Consider that a mere 15 years ago, Facebook’s famed growth-hacking team was celebrating a tremendous achievement: the average users’ time-on-site had just crossed 20 minutes per session.

Look around you now – don’t you miss the days when 20 minutes on social media was above average?

Unhealthy Industry Incentives

To make matters worse, content-creators online are facing the same unhealthy incentives, regardless of the types of content they create.

Intuitively, we might think that videos of cute animals are entertainment (and therefore should not be judged for their lack of nutritional value), whereas the news consists of real information. It’d be a fair distinction – if it were true.

But is it?

(yes, that’s a real headline from CNN)

What if news and entertainment have already converged and operate under the exact same incentives?

Cutting The Feed

Now that we understand the problem, let’s consider what the solution needs to look like.

There are different ways to develop a healthy diet, but most of them involve three distinct steps:

- Reestablish control over what you consume.

- Filter our things that are obviously bad.

- Decide how to balance out everything else.

Control is a prerequisite to everything. If your food intake consisted of whatever the nurse connected to your IV feed, any discussion of diet would be moot, wouldn’t it? You’d simply have no say in the matter.

So it’s imperative that you disconnect from feeds that are designed to take away your agency and to decide what you “might also enjoy”.

As a rule of thumb: if an algorithm decides that you (or your son or daughter) might also enjoy this item – don’t.

Cutting Out The Junk

Once the feed is disconnected, the next step is to remove the obvious junk out of your diet.

Mental junk can be divided into multiple categories, but what they all have in common is that they lack nutritional value.

The key question to ask with each type of content is “what can I do with this information that I couldn’t do without it?”. If you find it hard to come with an answer, perhaps there isn’t one?

Balancing Out What’s Left

Once you’re firmly in control and most of the junk is gone, there’s only one step left: balance. How much time do you want to spend consuming content? Let’s not leave this to chance – please take a piece of paper (or a spreadsheet) and write down a number.

Mine was two hours per day. What’s yours?

Is there a difference between your desired number and what you averaged over the past week?

Once you’ve determined the total amount, the next question becomes obvious – how do you want to divide this amount between the various types of content?

In a study from 2013, researchers compared people who witnessed the Boston marathon bombing to people who watched 6 or more hours of news coverage of the Boston marathon bombing. To the researchers’ surprise, the latter group had higher levels of PTSD than the former.

So the news might be useful, but clearly 6 hours of it is too much.

Going back to our food analogy – I love carrots, but I wouldn’t want to eat 8lb of carrots in one sitting. The same logic applies to content – I love Lex Fridman, but 7.5-hour podcast episodes can’t possibly be good for me.

A healthy information diet requires a reasonable balance between nutrients.

Too much of anything is bad for health.

About the Author

Alex Fink is the Founder and CEO of the Otherweb, an Austin-Based Public Benefit Corporation that aims to improve the quality of information people consume online. The Otherweb is also available as an app (ios and android), a website, a newsletter, or a standalone browser extension.