Nutrition, Aging, and the Masters Athlete

Let’s face it: getting older is not the most fun part of life. Lots of “cute” euphemisms are used to describe our bodies and a time in our lives that we never dreamed would happen to us as young adults: the middle-aged spread, over the hill, spare tire, muffin top, and beer belly. But these phrases don’t have to define us as we age. Something can be done to prevent and reverse weight and body composition changes that we used to think were inevitable.

The human body changes physiologically during aging. As we age, shifting hormones in both men and women impact our nutritional needs. For women, decreased levels of estrogen and progesterone generally mean an increase in cholesterol, abdominal fat accumulation, and an increased risk for conditions like osteoporosis. Men generally tend to have decreased testosterone and thyroid hormone levels beginning in their 40s, which can lead to weight gain as well as fatigue and loss of lean muscle.

We have all heard that our metabolism declines as we age. While this is true to some extent, it is not as significant as many of us believe. Our basal metabolic rate (BMR)—the number of calories we use daily just to maintain basic body functions like breathing—declines about one to two percent per year in older adults. BMR is at its highest when we are born and decreases as we age. The greatest decrease in our metabolism actually occurs from infancy to childhood. Let’s take a look at what that one percent change per year in BMR actually means. A 50-year-old woman who is 5’2” and 135 pounds has a BMR of approximately 1,300 calories per day. One year later, at 51, her BMR would decline by 13 calories per day to approximately 1,287 calories. Over time, this change can add up if our intake does not decrease as much as our BMR; on a more acute level, the change is fairly insignificant.

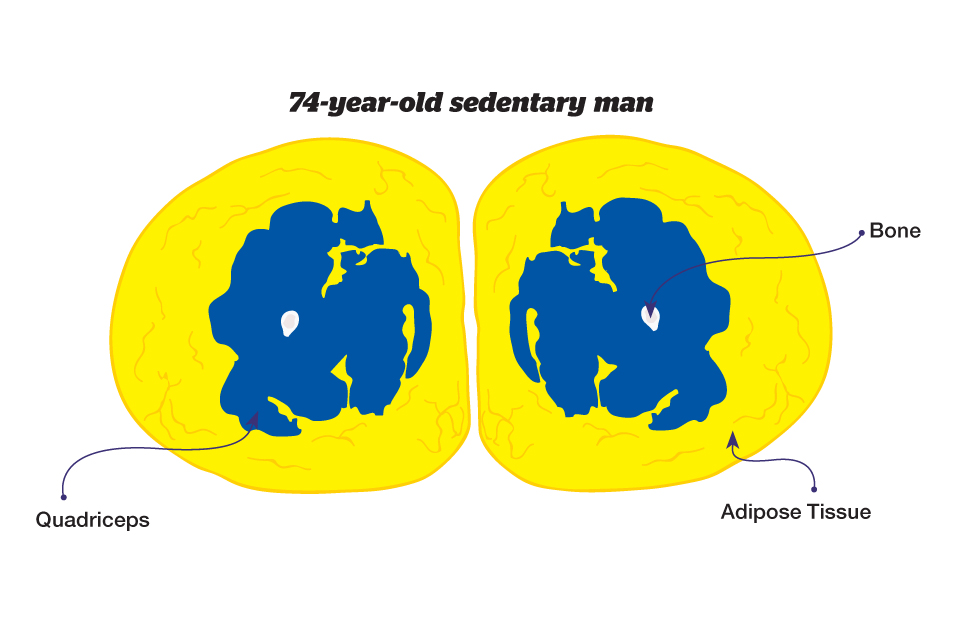

BMR also declines as we lose lean body mass. Lean body mass (muscle mass) is lost as we decrease the amount of physical activity we do and – most significantly – as we decrease weight-bearing activity in our older years. A decrease in muscle mass results in a reduction in overall calorie burn of about five percent per year, which impacts our weight more significantly. Our 51-year-old woman’s BMR would drop to 1,235 calories. The age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass is what your doctor may call sarcopenia. Lean muscle mass is the most metabolically active tissue in our body—it burns the most calories at rest than any other tissue. The more muscle mass that we maintain, the more our metabolism stays active and stable. The most significant reduction in BMR as we age happens from loss of lean body mass.

So what does this mean to the masters athlete and the weekend warrior? It’s essential for us to stay just as active in later adulthood as we did as young adults. Even if we have to trade short, fast runs for longer, slower runs (or even trade running for a jaunt on the elliptical trainer), we need to maintain our physical activity levels as we age. Some recent studies have shown that a decrease in aerobic capacity was the result of a decrease in training volume in older adults, not purely a result of the aging process.

More importantly we need to make sure that we maintain or even increase the amount of lean muscle mass we carry. Training with weights for as little as ten weeks can significantly impact lean body mass even in the most sedentary individual. One need not train like an Olympic weight lifter to increase muscle tone and lean body mass. Check with your local gym or recreation center to get a personalized plan that takes into account your activity level and your goals.

While these tips may help the casual athlete, there has been very little research on the needs of the vigorously active masters athlete. Some studies have suggested that the calorie needs of older, very active individuals do not differ much from their younger counterparts. Aging is not the main factor for figuring out calorie needs; instead, caloric intake is more closely related to the volume of activity.

If you are staying active, working out with weights, or doing other weight-bearing activities and still battling with your weight, it’s time to take a good, hard (and honest) look at your diet. As you age, you can continue to be active, participate in weight-bearing exercise, and maintain lean muscle mass. If you do this, you will be better able to maintain your weight and keep your metabolism humming. The more we maintain our activity levels, the less our chronological age matters—an active baby boomer can outperform a sedentary young adult.