Meeting Tarzen, The Grand Slackliner

I arrived at the Lady Bird Lake boardwalk around 11:30 a.m. For the last two weeks, I imagined this day as bright and sunny, but now, with rolling gray clouds, it looked like a misting system spraying over the city of Austin. I prayed this wasn’t an omen. After scanning the boardwalk, I saw Tarzen waving me down, so I approached.

“How you doin’ man!” I called out.

“Wonderful, today is a great day,” Tarzen replied, despite the ominous weather. His blue eyes beamed as he held out a fist. Something about a fist bump felt fitting for Tarzen; it was inviting.

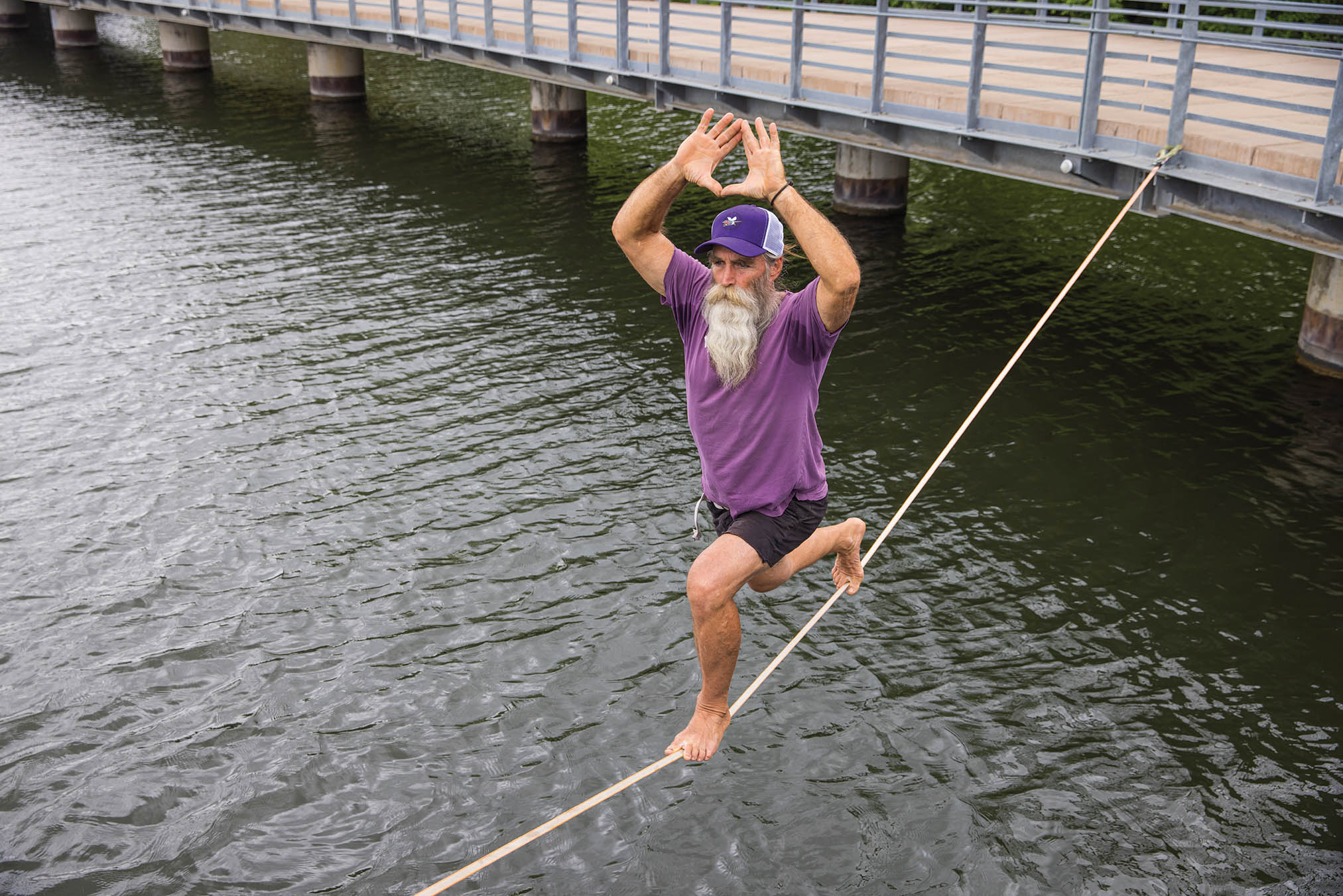

He wore a purple shirt, a hat and dark jean shorts. The most notable thing about him, though, was his rippling white beard. It was so long that his mouth disappeared; words seemed to simply slip through his mustache.

“You ready?” I asked.

“Follow me, I gotta grab some stuff,” he said.

We came to a stone wall. My jaw dropped as Tarzen, a 60-year-old man, swung himself over the wall and started jogging. “I parked right here,” he said. He opened his trunk and started pulling out buckets of rope. I watched him grab a brown mass and set it on the ground. “Mocha, go say hi.”

A brown chihuahua looked up at him as if it understood English, turned and waddled toward me.

“I call her Mocha Latte because she’s a latte dog to love,” he said.

She was trembling uncontrollably. After a few pets, she curled up on the stone wall and waited as Tarzen stacked his belongings onto a skateboard. Lastly, he scooped up Mocha and set her on it. And we were off.

We didn’t make it but 20 steps before Tarzen shared his life. He seemed eager to tell me about his hardships and wanted me to know about rehab center fights, the orphanage he was dropped off at and the solitary confinement he experienced at age 14.

These were details you might go a lifetime without knowing about someone, yet he was willing to share moments after meeting me. Looking back, I think it’s because Tarzen is a natural teacher; he wants you to learn from his mistakes. I figured teaching is his love language.

Soon, the Austin Fit team arrived for pictures and Tarzen explained his knot-tying techniques in great detail. After anchoring two points near some benches, he set down a mat.

“I thought we were going over the water?” I said. I should’ve seen it coming — Tarzen looked at me and, in all its clichéd glory, said, “You have to learn to walk before you run, buddy.”

And he was right. I expected to hop onto the rope and start inching to the other side, but as soon as I put pressure on my foot resting on the line, it began swinging uncontrollably.

“How do I stop that?” I said.

“You can’t hesitate; you have to stand but slowly,” he said. “Here.”

Tarzen stood on the rope in perfect balance. He held his arms above his head like a mantis and slowly twirled each wrist. No swinging, no trembling; just blissful stillness.

“It only takes little movements to change your body’s balance,” he said. “You move big, you fall big. Okay, try again.”

I practiced as Tarzen tied two lines stretching over the lake. One line was for me when I was ready. The other spanned three times as long and flapped in the wind like a flag. That one was Tarzen’s playground for the next four hours; he gathered crowds of passers-by to watch as he performed yoga poses, bounces and nonchalant gestures like twisting his mustache, all while maintaining his balance on a rope no wider than two of his toes, suspended over water.

He soaked up the attention and always thanked everyone for watching. If he could help it, he would strike up a conversation with them. No one was safe from his friendship.

After an hour of practicing, I decided to try the line over the lake. Tarzen helped me onto the line, holding out his hand for support. Then, he let go.

I balanced only for a moment; the next thing I knew, I was crashing into the cool lake.

As I treaded water, Tarzen climbed under the boardwalk and instructed me to follow. He hooked his feet onto L-beams, reached for protruding bars and pulled himself up and over the railing. I’ve never seen someone gracefully navigate hanging upside down as if he had an agreement with gravity.

For several hours, I watched Tarzen lap across the lines, showboating for joggers and never falling. Yet, the most impressive thing about him was his outlook on life.

“I think it’s important for people to learn to live life,” he said. “Too many people have forgotten that life is about doing what brings you joy. I live my life in a way that I can spend more time pursuing what I love and working just enough to give back to others with my skills.”

Saying bye to Tarzen didn’t go the way I imagined — but neither did saying hello. No tears, no embraces or grand gestures; just a simple fist bump. Here stood a man I’ve learned more about than some of my lifelong friends, yet he treated me just as he did our first meeting: with genuine friendliness. It felt like I’d see him tomorrow. I guess that’s a symptom of meeting Tarzen — you instantly become friends.