6 Simple Keys to Sports Recovery

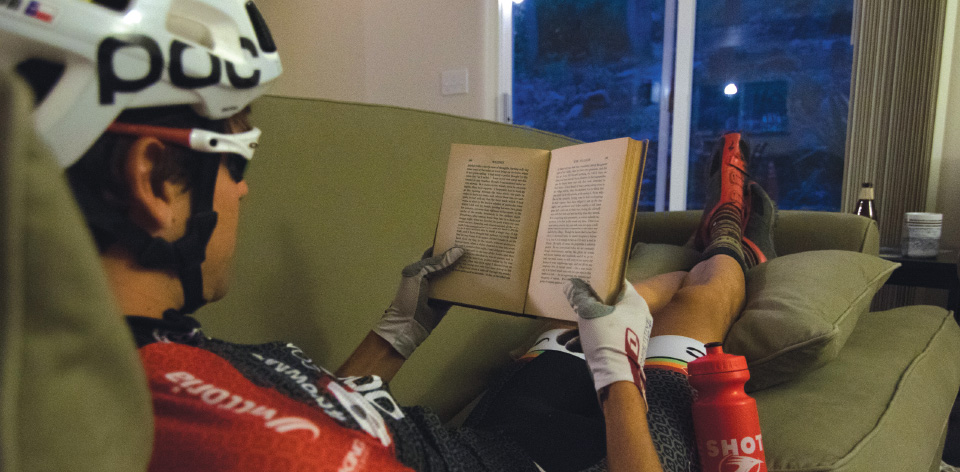

“You’ve got to rest as hard as you train.”

Being a professional athlete is all about tearing down your body and then rebuilding it all over again. While most of the population doesn’t have enough time or interest in eating, sleeping, and breathing their sport, they can benefit from learning how to recover properly between workouts. The old school knowledge states that if you’re not hurting, you’re not getting stronger. But that’s only half the equation. Often what sets athletes apart is not how hard they train, but how hard they recover. Here’s a list of tricks and techniques—in general order of importance—to make sure you’re getting the most out of every second of hard work you log.

Sleep

Surely no one is surprised to see this one at the top. A minimum eight hours are required for healthy individuals to feel rested and operate at full capacity. In my experience though, athletes often need more than that. For those of us with kids, demanding jobs, and other obligations, sleep is often the first thing to get sacrificed when you’re tight on time. Recent studies show that having a solid circadian rhythm is just as critical as pure number of hours spent asleep. (That is to say, you’re probably better off sleeping eight hours from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. consistently, rather than getting nine hours of sleep starting at inconsistent times.) Humans are creatures of habit and routine, and the more rested and in rhythm we can wake up each morning, the better our bodies and minds will perform.

Nutrition

We literally are what we eat, with most of our bodies completely new at the cellular level every six months. In my experience, there are no “silver bullet” diets that yield magical amounts of extra energy or health. Eating a balance of carbohydrate, fat, and protein is essential. One thing that often gets overlooked is timing. For optimal recovery, try to have a readily digestible (usually carb-heavy) meal on-hand within 30 minutes after the end of a workout. I like to cook large portions of white rice early on in the week, and then mix it with some stir-fried veggies or a few eggs for a quick way to get the recovery process started. After showering, stretching, and foam rolling (more on that below), I’ll usually cook up a more protein- and fat-rich meal to help with muscle re-building and longer-term energy. This second larger meal should be within 2-3 hours of the workout.

Activity Recovery

Much of recovery is about carrying healing nutrients to damaged muscles via blood flow and circulation. One great way to achieve this is through light exertion. On the bike, this could be 30-60 minutes of very easy spinning on flat terrain. I like to call these days “glass crank” rides, where you pretend your cranks are very fragile, and require a gentle spin in order to avoid breaking them. It’s also important to note that a faster pedaling cadence is more effective for these kinds of rides, as it reduces the strain on the muscles. A short 10–20 minute walk can achieve similar benefits.

Stretching

It’s one of the oldest techniques in the book, and that’s possibly one of the reasons studies so often try to debunk its benefits. I keep it in my evening routine simply because it makes sore muscles feel better. Create a 10-minute routine before bed each night that hits all the major muscles groups: quads, hamstrings, calves, hips, back, arms, etc.

Foam Rolling

Foam rolling is all the rage these days. Much like stretching, there seems to be plenty of research both “proving” and “disproving” the benefits of myofascial release, but I keep it in my bag of tricks as it makes my muscles feel better directly following a work out and the next day. If time allows, getting worked on by a massage therapist is preferred, but spending several minutes using a foam roller each evening certainly achieves many of the same benefits.

Compression

I am a true believer in compression wear as an aid in recovery. During the Whiskey 50 (a 50-mile mountain bike race in Arizona) this spring, my legs started cramping late in the race. I was in a battle with two other riders though, so backing off wasn’t an option. (Pedaling through cramping muscles is not only excruciating, but very damaging to myofibers.)

Directly following the race, I had to jump in a car and drive the seven hours home. In terms of recovery, this was a recipe for disaster. Just like every race though, I had packed my compression tights. I’m sure many of us have experienced swollen ankles and that achy feeling following a long drive or flight, regardless of hard exertion before. After peeling off my compression tights, the difference was striking: no swelling. Instead, compresion wear often leads veins and arteries to appear dilated; which means, they’re carrying fresh, healing blood to where it’s needed most.