It’s No Waltz Across Texas

One woman’s look at the Napoleon Ultra

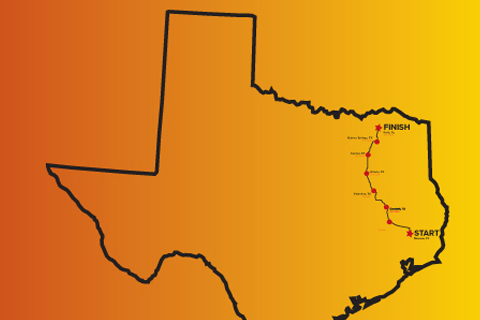

The East Texas scenery rolled out ahead; the exact location, a roadside rest area on Route 19, approximately 9 miles from the Love Civic Center in Paris, TX. For December, the day was unseasonably hot and the sun shone brightly on the sparsely populated, divided roadway. In the distance, a lone runner clad in an orange fluorescent shirt and black shorts came into view, making her way past the scrubby pasture land and smatterings of oak and pine. The runner is Rachel Wasilewski, a young woman from Wallingford, CT, and she is competing in the Napoleon Ultra, her first staged race. This balmy Friday afternoon is the final segment, Day Seven, and the rest area ahead, the last aid station before the finish line, marks mile 221 of the 230-mile run from Moscow to Paris. Wasilewski moved with a steady, shuffling gait and, after reaching the car, bent over, hands on knees, as the two volunteers welcomed her. She gave a few quick gasps—maybe they were sobs—groaned, and sank down into the camp chair provided, handing her hydration vest to be refilled while she ate the food she’d packed that morning, some 30 miles and many hours ago. The two volunteers moved with quiet, practiced efficiency, gently offering fruit and a variety of snacks to the weary woman. Wasilewski focused on her mix of nutrition and asked a few questions about the stretch ahead and the other runners, all of whom were ahead of her. She was not looking forward to the next hours. Her legs and feet hurt; all that was keeping her going was her desire to GET THIS DONE and stop. After only a few moments, she stood up, stretched her legs, and, after collecting a hug and encouragement from the crew, shuffled off down the shoulder of the road.

Wasilewski, along with the other eight runners who took on the new Texas stage race, finished that day. The journey took her a total of 53 hours (while she finished last on that final day, she wasn’t the slowest runner; two Frenchmen had totals in the 57-hour range). It says a lot about the nature of this particular sect in the religion of long distance running that all those who had completed the course waited for Wasilewski to come in; the winner, Jenni de Groot (Netherlands), had been done for almost four hours that day yet, when it was reported that Wasilewski was approaching, de Groot hopped on a bike and cycled off to escort her for the final mile or two. The rest of the runners made their way to the roadside, scanning anxiously; the cry arose—“There she is!”—and cheers of “allez, allez” broke out among the multilingual crowd. After Wasilewski rang the finishers’ bell, all crowded around, taking pictures and giving hugs as though she’d been the first one to finish and they merely spectators.

Wasilewski, a therapist, yoga teacher, and mother, is no stranger to running and endurance events. She’s done half and full Ironman-distance triathlons, several 50K (31 miles) races, marathons, and hiked the 250-mile John Muir trail over three weeks. But she had never done a stage race, a running event that lasts several days and usually covers marathon to ultra distance (anything beyond 26.2 miles) each day. Unlike the other runners in the event, Wasilewski had never met race director Russell Secker; she’d never been to Texas. Like Secker, who’d come across stage racing through a book and become fascinated, Wasilewski had become enamored with the idea of taking one on and decided to give it a try; the new Napoleon Ultra fit both her budget and her vacation allotment. She later gave her reasoning for taking on the distance in her blog: “I wanted to push the physical limits of my body, to see what it is that I’m capable of… I needed to have time to be with myself. I needed to have a time for thought, a time for no thought, a time for meditation.” What she got was “seven days of running meditation, an endeavor that broke down and through my physical body to the heart of raw, pure emotion; down to my bare soul of what is true and real.”

Rachel Wasilewski stood out at the kick-off luncheon at the French Legation in Austin. She was the youngest of the runners at 30 and looked even younger, like a fresh-faced schoolgirl. She laughed to say that just a few days before, she’d run at home in a snow storm and she’d travelled that day wearing a down coat, so the more than 70 degree temperature in Texas was quite a contrast. The international runners were all in their 50s and 60s; she could easily have passed for someone’s daughter. Wasilewski stood apart in her dietary restrictions as well; being vegan, the pizza with cheese didn’t work. As one with gluten issues, the bread was out. She passed on the wine. She explained that she’d anticipated nutritional issues and had packed her own food for the entire trip. While she was excited and full of anticipation about starting, there was a bit of fear (had she prepared enough?) and awe (the rest of the runners had an incredible amount of experience, some with hundreds of ultra stage events) in the mix. After lunch and Secker’s race presentation, Wasilewski set off with the group for the drive to Crockett and promised to stay in touch.

Each night, Wasilewski wrote in a journal, even though she was dead tired; afterwards, she was glad she’d forced herself to complete the exercise. “Each day was different yet the same,” she reminisced in a follow-up phone conversation, a month after finishing. “The days seemed so long yet they went by so fast,” she said, and details blurred: “Time gets warpy.” While she remembers things, she’s not always sure exactly on what day they happened. Wasilewski recalled de Groot passing her once, stopping, and then coming back to hug her; another day, Rob Secker, the race director’s son and primary aid station volunteer, saved her a banana and walked beside her for a comforting amount of time. These little acts took on big significance as her body and spirit sank under the grueling effort. The hours on the road alone were a mental challenge (for safety’s sake, there was no distracting iPod and the small group was often dispersed over miles). For the first two days, her mind was busy with random things and the runner spent a lot of time thinking about what she had to eat up ahead and doing “bad math” regarding mileage. Finally, Wasilewski’s mind quieted and she reached the point where “all I’m doing is running,” the destination she’d been seeking all along.

Looking back, Wasilewski mused that there is no real way to train for this experience. The seasoned runners offered simple nuggets of wisdom here and there: don’t go out too fast because you can hurt yourself; don’t go out too slow because you can hurt yourself; listen to your body. Secker pulled her aside to inquire, “What are you doing for your feet?” He recommended coating them in Vaseline each day; Wasilewski took the advice and had no blisters “but my feet are peeling in sheets now,” she laughed ruefully. De Groot offered comments that touched Wasilewski immensely: “Jenni was very humble and kind. I would hear her coming up behind me (the faster runners started last each day and gradually caught up to those ahead). One time, when I was hurting, she said to me, ‘I would do this for you if I could, but I can’t—you have to do this on your own,’ which was somehow an assurance. And then, on the last day, she told me as she rode next to me on the bike, ‘Think of your family, how proud they’ll be,’ as I struggled to finish the last miles.”

The run took a toll physically; afterwards, Wasilewski’s body was full of fluid and she suffered from night sweats and interrupted sleep. She felt hip and knee pain, which she largely chalked up to the steep camber encountered on the shoulders of narrow county roads and the relentless pounding of that much hard surface mileage. As a physical therapist, she laughed to say that she should be doing her knee rehab protocol but “I’m not the best patient.” While she was back to biking and swimming, she’d only done a few short runs of 3 to 5 miles in the month after reaching Paris.

She’s still mentally processing the run, turning events over in her mind, talking it over with friends, and writing about it in her blog. What Wasilewski’s come to realize is that the journey was more of a life experience than a running event. “Training and doing the event kept me sane in a difficult time,” she stated. “The first two days were fun, but the days after were a huge mental push just to finish. I found that the ultra was a mirror reflection of what was going on in my life, and I needed to prove to myself that I am whatever I need.” It also changed her perspective of what running can be—more than a physical activity, the running became an emotional outlet akin to yoga. When she tried to explain to a friend, he said he understood: “Stopping became more painful than keeping going.” Mentally and physically, quitting just wasn’t an option.

Will Wasilewski come back to the Napoleon Ultra or do another stage race? Her response was thoughtful and reserved. “It would be interesting to do another one,” she said, “because if I did it again, it would be a totally different experience. I’m not the same person anymore.” She had a new challenge on the horizon, a solo hike from San Jose, CA, to the coast, which she anticipated would cover 70 miles over five days. Her trek along the Appalachian Trail years ago had been a learning experience about equipment and camping and not much of a source of mental peace, but this journey, she hoped, would be different.

Back at work, a client observing her sticker-covered Nalgene water bottle recently said to Wasilewski, “I hear you run marathons.” When she answered yes, the follow-up question was, “How long was this last one?” People often don’t realize that “marathon” doesn’t just mean “long”; it’s a specific distance of 26.2 miles. Wasilewski softly replied, “230 miles.” The client’s response was one of incredulity, though the young runner disagrees with that reaction. “It’s all a matter of perspective,” she explained. “Whether 10K or half marathon or ultra, it’s all relative. I only started running six years ago; I started out playing soccer in high school but became unfit in college. I used the excuse ‘next semester’ to put off getting in shape until, one day, I put on some sneakers.” She laughed to recall that she couldn’t even make it around the block that day. As to having now run 230 miles over seven days, she’s still “wrapping my mind around that.” But one thing she firmly believes: “If I can do it, anyone can do it.”