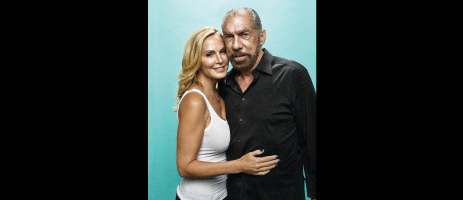

At Home with John Paul and Eloise DeJoria

John Paul and Eloise DeJoria have a lot of experience as philanthropists. He became a philanthropist as a small child, and she learned from her father how to give back even when traveling for business. They love to talk about the lives they are changing, but not so much about how much they give—though they give a lot. DeJoria is so understated about his giving that Fortune Magazine even named him among their list of “Lesser known billionaire givers.”

DeJoria signed on to Warren Buffet and Bill Gates’ Giving Pledge, a program described as “an effort to invite the wealthiest individuals and families in America to commit to giving the majority of their wealth to philanthropy.” In his Giving Pledge DeJoria tells the same story he told Austin Fit Magazine—that he became a philanthropist at six years old.

“We didn’t have very much money but we’d go to downtown Los Angeles to look at the Christmas decorations in the windows,” he said. One year [my mother] gave my brother and me a dime and said, ‘Now each of you hold half the dime and go over there and put it in that bucket.’ So we held out the dime, walked over and put it in the bucket. But we said, ‘Mom, that’s a dime. That’s two big Coca-Colas, three candy bars, why put it in that bucket with that man?’ She said ‘That’s the Salvation Army and remember this, sons, as you grow up: there is always someone that is in need more than you are. We try and give whatever we possibly can.’

“That stuck with me,” DeJoria said. “Philanthropy is not necessarily how much money you have to give away, it’s being involved and participating. In most all the charitable work we do, we physically participate.” A self-made billionaire, DeJoria said philanthropy became a way of life for him even during times when he had no money. In his 20s, a period he refers to as his “biker years,” he would go to Griffith Park in Los Angeles at Thanksgiving and Christmas to volunteer serving food to homeless people and their families.

DeJoria’s beginnings are well-documented—a first-generation American raised in poverty in a European immigrant neighborhood in Los Angeles, he worked a variety of jobs, rising through the ranks at Redken and then starting his own company, Paul Mitchell, with his friend, the hairdresser Paul Mitchell. The story is that they started the company with only $700 dollars and that the packaging for Paul Mitchell products is black and white because they couldn’t afford colored ink.

He still owns and runs Paul Mitchell hair care products, salons, and schools. He started and still runs Patrón tequila. He has repeatedly asked Fortune Magazine not to name him in their list of the wealthiest people, but the most recent list ranks him at number 212, with a fortune of more than $4 billion.

He owns 10 houses, but he calls Austin home and that’s where he and his wife, Eloise, chose to raise their son, John Anthony. The DeJorias have a combined total of six children and 10 grandchildren. Their teenager, John Anthony, is the child the couple had together and one of the reasons they live in Austin. “We chose Austin for family values,” DeJoria said. “It’s a better place to raise a kid,” he said. “We looked the whole world over.”

Eloise, a native Texan who had lived in Austin for seven years before moving to Los Angeles, agrees and was in favor of having Austin as a home base for additional reasons.

“I really wanted to be there for the special elder people in my life,” she said. “[People such as] Edith Royal, who is a very dear friend of mine from my young 20s, and my mom, who is an hour away.”

Eloise met DeJoria on a blind date 20 years ago. They still have a palpable chemistry between them, teasing each other and laughing with impish but genuine affection. This connection comes through in all facets of their conversation. While discussing health and fitness, Eloise pointed out that, although she works out every day, she learned over a decade ago that nutrition could have as profound an effect on appearance as exercise. DeJoria interjects, “Eloise doesn’t drink. You know, he jests, “I’m 67 years old, she’s 77 years old—can you believe this?” Similarly, before he could explain what constitutes his regular exercise regimen, Eloise said, “He chases me around.” Their unpretentious manner and genuine interest in others is evidenced by the friendship-style relationships they have with their staff and the unguarded demeanor they share with new people they’ve just met. They enthusiastically shared details of their personal diet and exercise experiences.

The DeJoria’s elegantly minimalist home on Lake Austin has a gym which, along with all the usual gym equipment, includes a heavy rope suspended from the ceiling. DeJoria, who started out in athletics as a gymnast, had the rope installed as part of his fitness regimen, which also includes military push-ups—in fact, he brought out his Navy SEALs push-up equipment—two round, flat objects, each with a handle. Holding one in each hand, he demonstrated, doing a push-up and twisting the handles each time.

“These are very difficult,” he explained and then offered them to others to try, but he had no takers. “I do two sets of 25, twice a week and then I do five [dead-hang] pull-ups twice a week.” DeJoria, 67, has an impressively lean, fit frame.

Eloise, 54, has her own fitness regime, which consists of swimming, running, stand-up paddle (SUP), and Bikram yoga, working out every day. She describes herself as “outdoorsy” and uses many of Austin’s natural features; she has multiple stand-up paddleboards. She also walks and runs on the trail at Lady Bird Lake. She’s so serious about her workouts that she has even conducted meetings during a workout.

“[Recently] someone wanted to talk with me about charities and I said ‘Okay, but you’ve got to come swim with me,’” she said. “It was a great visit; we swam for an hour and half.”

The couple was recently featured on a television special with Barbara Walters, who highlighted the five-star chef they employ. Diet is very important to the DeJorias.

“We’re shooting for eating raw a couple of times a week and vegetarian a couple of times a week,” Eloise said. DeJoria concurred, adding that they try not to have meat more than twice a week.

“We eat a lot of vegetables,” he said. “It’s very important to have organic foods—and small portions. I find the secret is small portions.”

His adherence to a healthy diet for himself and his family has been infused into his philanthropy as well.

One project he’s most excited about is his Grow Appalachia initiative. One of his executives who grew up in that region pointed out to DeJoria how difficult it is for out-of-work generations of coal miners to sustain their families, much less eat healthy food.

“[When] you have food stamps, you buy what you can,” DeJoria said. “Sometimes when you have little money, the food you buy is not the best for you: white flour, processed foods, 99-cent burgers. A lot of these people put on a lot of unnecessary weight.”

A self-made man who never had a mentor—“it might have been easier if I had,” he said—DeJoria takes a self-starter approach to his philanthropic endeavors as well. He went to Appalachia, interviewed people himself, and found Berea College in Kentucky to partner with him.

“I [took] this on personally,” he said. “I started [the] program, where I would buy the tractor, the hoes for little farms. I would pay for whatever equipment they needed and I would pay for people to help out, and Berea College would provide volunteers and engineers and help put this into effect.”

He started the project two years ago with $150,000 to test 100 gardens. Those test gardens fed fresh, healthy vegetables to 2,700 people. In addition to cultivating crops, Grow Appalachia provides training in preserving food by showing participants how to can vegetables to last through the winter. With more gardens and the tools and technology provided by the project to keep the food they grow, more people are eating (and eating better), and their health is improving, according to DeJoria.

The success of the pilot led DeJoria to quadruple the amount of gardens with a goal to feed half of Appalachia—or help them feed themselves—within five to seven years. He says that after two years they are on target to reach his goal of feeding 50 percent of Appalachia—about 100,000 people. More, the gardens are producing enough for the farmers to sell the excess at farmer’s markets.

Part of DeJoria’s philanthropic philosophy is that his personal participation in the project is important. Earlier this year, he flew his family to see the farms and meet the people involved with Grow Appalachia.

“I wanted Eloise and John Anthony to see it,” he said. “I may be paying for all this and organizing it, but I want you to feel what I’m doing here.”

Seeing the farms and meeting the people had a profound effect on Eloise. “It really changed me. I can’t even talk about it; [seeing] the tears in the eyes of these people we were helping and how good it felt to them to give us products of their gardens. They had whole families [there] and had a picnic for us. We all love supporting ourselves and helping others; we just don’t always have the tools. If I hadn’t gone, it would be completely different, just sending money versus actually going and being involved.”

Instilled in the ethos of each of his companies is his mantra that “success unshared is failure.”

“Everyone knows Patrón, they know Paul Mitchell, they know John Paul Pet, but these are different companies and part of their culture is giving back,” he said. DeJoria’s enthusiasm betrays his pride in and passion for having his companies operate with an eye to philanthropy. Animated, he leans forward to explain: “When we started the company, we started doing [charitable work] and we still do it. So if these companies can have a culture of giving back, the sharing of success, [other] companies can do the same thing; individuals could do this, as we pointed out earlier by just participating in something. Even if it’s something as innocent as a smile, you’re philanthropic. You’re making someone else happier; you’re transmitting smile happiness to someone.”

His Paul Mitchell Schools, with 110 in the U.S. and several abroad, include fundraising for local causes as part of the educational process. The school in Thailand had a fundraiser to send relief to Haiti not too long ago. He remarked on the creativity of the students.

“The most amazing was our school in Orlando, Florida,” DeJoria said. “They had a Topless Carwash. Before you say anything, picture going down the street and here are all these young, good-looking kids out there with signs, ‘Topless Car Wash.’ Everyone wanted to see what was going on. The minute you pull in, they hit your car with soap and water immediately. But they don’t do the top of your car. You say, ‘Wait!” But they say, ‘It’s a topless car wash, that’s $5 extra, but it all goes to a charity. That’s why we’re here.’ They raised $1,600 in three hours. Topless car wash. They come up with some really creative things.”

DeJoria was just back in Austin from New York where he had addressed the United Nations on the topic of sustainability. He said it was the first time the U.N. had business people and philanthropic volunteers all together.

“The core message was that it works. I gave them some examples, the biggest one I gave them was around the JPSelects.com web site,” he said. Launched a few months ago, the site allows people to purchase approved “sustainable” products, with a portion of the proceeds donated to charity. “Every company [with products] on the site has to be approved that it has sustainable practices, that they take care of their people, and they do something to make their city or the country a better place to live,” DeJoria said.

DeJoria’s efforts are not unnoticed. While in New York, he was interviewed by NBC, FOX, FOX Business, Bloomburg, the New York Times, Maxim, and taped the 20/20 interview with Barbara Walters.

In Austin, the DeJorias are involved with many groups, including Help Clifford Help Kids, Paramount Theater, The Long Center, Austin Children’s Shelter, Austin Film Festival, and Ann’s Wolfe Pack. In 2011 they set up their family foundation, JP’s Peace Love & Happiness Foundation. In addition to running DeJoria’s philanthropic work domestically and internationally, the Foundation is sponsoring what has become an annual hill country motorcycle ride primarily benefiting Austin’s Club 100.

“We wanted to give John Paul a birthday party,” Eloise said. “He wanted to use his birthday to give back, so he and his friend Gary Spellman created the Peace Love Happiness ride. It’s a really cool thing because he gets his friends like Peter Fonda and Robbie Knievel to come ride. Our governor [Rick Perry] rides with him.

“It’s something that everybody can get involved with,” she said. “If you don’t want to ride a motorcycle, you can always follow in a car.”

“[The ride] is the weekend closest to April 13,” DeJoria said. “We go out of the Harley dealership south of town; we go out in the country for a cruise and ride about 100 to 120 miles. Then we stop somewhere for a great lunch and hang out a little bit. [We have] anywhere from 200 to 500 riders, depending on the weather.”

“There’s a VIP part, too,” Eloise said. “I’m going to try to get Cher to come in. Cher rides her own bike.”

For information about the 2012 Peace Love Happiness ride, scheduled for Friday, April 13, 2012, visit www.peacelovehappiness.com.