Are You Supplementing Your Gain?

Chris Tsai is comfortable living life on the edge. After all, he spent his teenage years as a competitive BMX racer. “Now I get that rush from lifting weights to the max,” Tsai said.

Tsai, a fifth-year senior studying business at the University of Texas, is like many college-aged fitness enthusiasts who are reaching for pre-workout supplements to jumpstart their training sessions. Marketed as “powdered energy” and “miracle in a bottle,” products such as C4 and Adrenolyn are becoming popular workout enhancers and are available at local nutrition retail shops and online.

Both C4 and Adrenolyn contain forms of creatine and caffeine. These stimulants provide immediate performance boosts, such as increased stamina and focus, but questions remain about how positively they actually affect the body. “It probably depends on your outcome,” said Dr. Matthew Brothers, a professor of exercise science at UT. “There are certainly benefits provided to exercise capacity, but there could be potentially harmful effects on other things.”

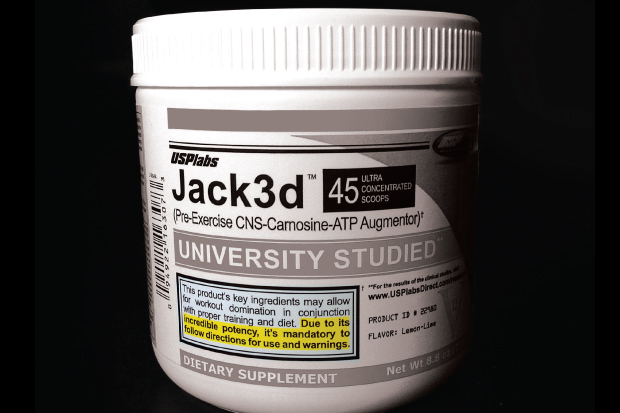

For instance, GNC stores nationwide were recently required to pull the pre-workout supplement Jack3d from shelves after the Food and Drug Administration ruled in April that it was not a legal dietary supplement because it contained dimethylamylamine (DMAA), a stimulant similar to amphetamine that could raise blood pressure and potentially cause heart attack. Jack3d was thrust into a national spotlight in the summer of 2011 following the deaths of two Army soldiers who had heart attacks during exercise. DMAA was found in their systems, and, in the aftermath, the Defense Department removed all products with DMAA from stores on military bases.

Tsai says he has used Jack3d and never felt “bad” while taking it. Currently, he takes Adrenolyn, a pre-workout supplement manufactured by BlackMarket Labs and advertised as not for “the faint of heart or frail of body.” Adrenolyn contains caffeine and synephedrine, which BlackMarket Labs describes as “a healthier substitute to ephedra.”

“I feel like I can recruit more muscles when I take it,” Tsai explained. “When I don’t, the mental connection is missing. The mind-muscle connection is not as strong. I feel the maximum effects on my high rep, high volume days.” Tsai said that he relies on proper water intake; he understands that dehydration is a possible side effect and he noted that with pre-workout supplementation, it’s important to understand the ingredients.

Creatine, for instance, primarily helps maximize strength. It has long been a popular supplement and can even be taken by itself. BCAAs are branched amino acids than can reduce muscle tissue breakdown and lead to new muscle growth. Caffeine and other stimulants work as cognitive enhancers and are often the common denominators in these pre-workout supplements dominating today’s market. “From a practical standpoint, you want to be cautious about anything that is going to alter your heart rate, aside from the exercise itself,” advised Dixie Stanforth, a senior lecturer who developed the personal training curriculum at UT.

For the longest time, Ben Keeler mixed his own pre-workout supplement cocktail, a combination of amino acids and creatine. “There’s just a lot of stuff out there that you don’t know what it is,” admitted Keeler, an economics senior at UT.

In fact, Driven Sports Inc., the manufacturer of the pre-workout supplement Craze, recently suspended sales and production of its product following a Drug Testing and Analysis report. In the published journal, scientific researchers claimed to find a methamphetamine-like substance in Craze samples. The substance was also not listed on the product’s ingredient label.

Keeler, who is training to ride with the Texas 4000 for Cancer group to Alaska this summer, now takes C4 as his pre-workout booster. He said that it provides a similar feeling to coffee, and the fact that it’s available at places such as Costco makes it seem legitimate.

“I try to do my research,” Keeler said. “I don’t want to take anything that will give me heart failure.”

FDA’s Role in Regulating Supplements

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulates both dietary supplement products and dietary ingredients. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 provides that the manufacturer of a dietary supplement or ingredient is responsible for “ensuring that the product is safe before it is marketed,” but the FDA is responsible for taking action against any “unsafe dietary supplement product after it reaches the market.”

The DSHEA requires that a manufacturer or distributor notify the FDA if intends to market a supplement that contains a “new dietary ingredient.”

Manufacturers are not required to register their products with the FDA or get FDA approval before producing or selling dietary supplements. They must make sure that product label information is truthful and not misleading. Each dietary ingredient contained in the product must be identified on the label.

In addition, the manufacturer, packer, or distributor whose name appears on the label is required to submit to the FDA all serious, adverse event reports associated with use of the dietary supplement.